The never-ending fight for justice: A review of the year after the humanitarian pardon was granted to Fujimori

- Blogs

8 February 2019

Maria Rodriguez

Voluntary legal adviser

On December 24, 2017, the then President of Peru, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, granted a humanitarian pardon to former Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori. In 2009, Fujimori had been convicted by the Special Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Peru to 25 years in prison for the crimes of qualified and aggravated homicide and kidnapping related to the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres.1

The Barrios Altos massacre occurred on November 3, 1991, in the district of Barrios Altos, in Lima, Peru, where six members of the paramilitary group called “Grupo Colina” arrived to a town-hall meeting and massacred 15 people, including a child, and gravely injured four others.2 The La Cantuta massacre occurred July 18, 1992, early in the morning, when members of the National Intelligence Service of Peru (SIE) and of the Army Intelligence Directorate (DINTE) burst into the dormitories of the National University Enrique Guzman y Valle while its residents were sleeping. When the sweep was over, nine students and a professor were kidnapped and taken to an isolated location outside of Lima. They were subsequently killed and buried in unmarked graves.3

Both these crimes occurred during Peru’s armed conflict with the terrorist groups Sendero Luminoso (PCP-SL) and Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA), which lasted from 1980 to 2000.4 The Special Chamber that confirmed Fujimori’s sentence in these two cases characterized these crimes as crimes against humanity.5

APRODEH – the organization I have been working with since June 2018 – leads the representation of the victims in the Barrios Altos and La Cantura cases, along with three other NGOs, both at the national and at the international level. I was very lucky to arrive at APRODEH just as they were preparing the formal challenge against the pardon to be presented at the Supreme Court of Peru. I have thus witnessed firsthand the internal litigation process, and the toll this process and international litigation has taken on the victims.

The granting of this pardon unleashed a political crisis in Peru and reignited the longstanding battle of the victims and family members of these two emblematic cases against impunity. In this text, I seek to explain the steps that family members and their representatives have had to take in search of justice and to honor the victims. A year after the granting of the pardon, the litigation process has yet to bring a final resolution of the matter.

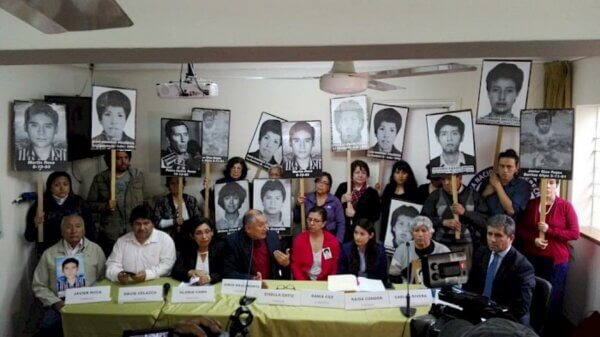

Family members of victims of the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres and their lawyers giving a press conference on October 3, 2018 after the pardon was declared invalid by the Supreme Court of Peru

The first step: Turning to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for redress

Many saw Pedro Pablo Kuczynski’s decision to grant this pardon as a political maneuver to avoid being forced out of office by the Fujimorist majority-controlled Congress. And indeed it was,6 although Kuczynzki was nonetheless forced to leave office shortly thereafter.7 Besides the political nature of the pardon, Kuczynski’s decision was also a slap in the face for the victims in these cases. What it said was: politics is much more important than the justice you deserve.

Thus, in the face of such a discretional decision by the President of Peru, which could not be directly challenged at that moment,8 the victims of the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres were forced to turn to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR or “Inter-American Court” or “the Court”) in search of redress. Specifically, the victims asked the IACtHR to order the State of Peru to remove all legal obstacles that impeded effective compliance with the sentence pronounced against Fujimori by the national courts in 2009. In other words, the victims were asking that Fujimori return to prison to serve his sentence in its entirety.

Furthermore, the victims asked for a declaration from the Inter-American Court stating that the pardon granted was contrary to the duty to investigate, judge, and sanction those responsible for grave human rights violations, an international obligation enshrined in article 1.1 of the American Convention on Human Rights and developed by the jurisprudence of the IACtHR.9 Indeed, for the victims and their representatives, the pardon had been given illegally, arbitrarily, without consideration for the victims’ right to justice and with the purpose of leaving these crimes unpunished.

Since the IACtHR has judgments on both the Barrios Altos and the La Cantuta massacres (Case of Barrios Altos vs. Peru. Sentence, 2001;10 and Case of La Cantuta vs. Peru. Sentence, 200611), turning to the Inter-American Court to challenge the legality of the pardon that had been granted was a viable and useful route for the victims.

Insofar as the pardon granted infringed the reparations ordered by the Inter-American Court in these judgments, the victims and family members were entitled to use the Monitoring Compliance with Judgments section of the IACtHR to ask the Court to review the pardon. In essence they asked the Court to analyze whether the circumstances of the granting of the pardon were contrary to Peru’s international obligations and if so, to order the State of Peru to redress the situation.

International concern over the issue of impunity in cases of grave human rights violations

Having received the request for a Monitoring Compliance with Judgment hearing by the victims’ representatives, the Inter-American Court convened a hearing on February 2, 2018.

The central question that the Inter-American Court had to answer was essentially whether in cases of grave human rights violations humanitarian pardons can or should be granted. In light of the importance of this question and the political climate in Peru that allowed for the pardon to be granted, the upcoming hearing at the IACtHR garnered a lot of international attention.

Many international organizations were very concerned with the perpetuation of cycles of impunity. The Inter-American Court received around 16 Amici Curiae from various NGOs,12 including one from Lawyers Without Borders Canada, written in collaboration with five other organizations.13

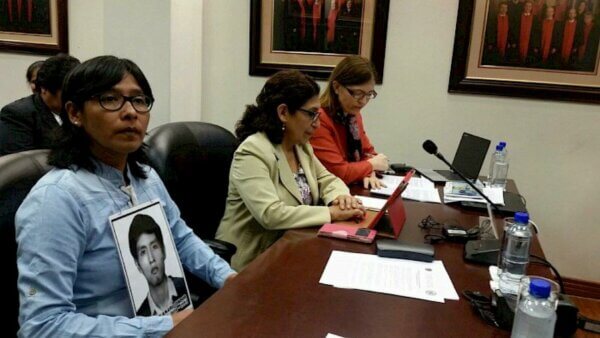

A family member of a victim of La Cantuta at IACHR after testifying and her lawyers.

At the IACtHR’s hearing, the victims and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights argued that the pardon granted was contrary to the state’s duty to investigate, judge and sentence those responsible for serious human rights violations, and thus it infringed the victims’ right to justice. Moreover, they argued that pardons or other sentence-reduction mechanisms are neither applicable nor appropriate in cases of crimes against humanity.

Conversely, the essence of the state’s position was that the pardon had been granted in accordance with the domestic legislation and that the victims should have used the available internal mechanisms in Peru before turning to the international tribunal.

The Inter-American Court’s resolution of May 30, 2018 – a win on paper, but a new burden on victims’ shoulders

The Inter-American Court issued the awaited and critical decision in this case on May 30, 2018.14 In this decision, the IACtHR established clear international standards applicable in cases of crimes against humanity regarding the granting of a humanitarian pardon.

Furthermore, the Inter-American Court analyzed the different ways in which a detained person’s right to integrity can be protected; these do not necessarily imply pardoning their sentence. It also established the essential elements and factors that must be duly balanced when granting a pardon, and it reiterated the importance of the international right to access to justice for victims of grave human rights violations.

Yet, in its resolution, the IACtHR did not specifically decide whether the pardon granted to Fujimori contravened Peru’s international obligations and infringed the victims’ rights to justice. Rather, the Inter-American Court asked that this issue be brought up for revision before the Peruvian judicial system.

The victims of the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres thus welcomed the Inter-American Court’s resolution reluctantly. Even though the IACtHR established important international standards regarding the use of sentence-reduction mechanisms in cases of crimes against humanity, the victims felt that by asking that the pardon be reviewed by the judicial system of Peru, the Court had put a new burden on their shoulders.

Gloria Cano, lead lawyer from APRODEH, giving a statement right after the formal challenge to the pardon had been presented to the Supreme Court of Perú

Instead of having the victims bring a formal challenge to the pardon at the national level, the IACtHR could have specifically requested that the State initiate an internal review process in the national courts. Further, it could have required the State to inform and demonstrate to the IACtHR whether the pardon had been granted in conformity with international standards; and, if not, to provide information on the steps being taken to redress the situation.

However, this was not the case and the internal litigation process that the victims and their representatives have had to lead would prove to be very taxing and time-consuming.

The formal challenge against the humanitarian pardon in the national courts

On July 20, 2018, the victims of the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres presented to the Supreme Court of Peru a request for review of the pardon. They asked specifically that a conventionality control be exercised. In other words, the victims asked that the Supreme Court consider whether the presidential order that granted the pardon complied with the American Convention on Human Rights, with the IACtHR resolution of May 30, 2018, and with Peru’s other international obligations.

Victims of La Cantuta and Barrios Altos, accompanied by their legal representatives, standing on the steps of the Supreme Court of Peru after the hearing of September 21, 2018.

A hearing took place on September 21, 2018. The victims’ representatives and Fujimori’s lawyer presented their respective oral arguments.

It was then on October 3, 2018, that the Supreme Court of Peru handed down its decision on the matter. In its 225-page resolution, the Court declared that the pardon had been granted in contravention not only of international standards, but also of the domestic legislation and procedures that allow discretional presidential pardons to be granted.

As such, the Supreme Court declared that the pardon was not valid and thus produced no legal effects. The Court’s decision was of a retroactive nature, which meant that Fujimori had never been legally pardoned in the first place, and had to return to prison immediately.15

This resolution was an important win for the victims of Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres. They felt that while they were still carrying the burden of the fight for justice after almost 30 years, their voices had been heard and at least formal justice was on the way.

However, on the same day as the Supreme Court resolution, Fujimori was rushed to the hospital. He claimed he had suffered a medical crisis.16 The feeling afterwards among victims was that until Fujimori was brought back to the penitentiary institution to continue serving his sentence, the win before the Supreme Court would merely be symbolic and Fujimori would still be benefitting from impunity.

Victims and family member of La Cantuta and Barrios Altos, accompanied by their legal representatives outside of the Supreme Court of Peru after the appeal hearing of December 17, 2018.

Moreover, Fujimori’s lawyer immediately appealed the Supreme Court’s resolution – which is his right. Yet, since the request for appeal was granted, this meant that the victims still had to continue fighting for justice in the courts.

The Special Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court of Peru, tasked to hear the appeal, scheduled the appeal hearing for December 17, 2018, nine days shy of the anniversary of the granting of the controversial pardon. During this hearing, the parties were given time to present their oral arguments, and the panel of judges asked various questions.

On January 23, 2019, Fujimori was finally discharged by the hospital where he had been staying, apprehended by the National Police and brought back to the Barbadillo prison.17 This came only due to the perseverant and numerous requests made by the victims’ representatives to the Special Criminal Chamber asking for the execution of the October 3 decision. Fujimori thus spent 113 days in the hospital following the annulment of the pardon before he was finally brought back to the penitentiary institution where he was supposed to finish serving his 25-years sentence.

The re-incarceration of Fujimori is a powerful and symbolic achievement, and a matter of celebration for the victims of the case.

Nonetheless, at the early start of February 2019, what everyone is expectantly waiting for is the final resolution of the Special Criminal Chamber. It is the last judicial body before which the pardon can be reviewed within the national system. As such, the final decision is extremely important and will have a huge symbolic weight.

Either a certain form of justice will be attained through a judicial recognition of victims’ right to justice, or Fujimori will return to freedom, enjoying impunity for the crimes he committed. In the latter scenario, the victims would need to continue their battle at the international level in front of the IACtHR.

The former is what the victims are really hoping for, but it would still only be a form of formal justice. Indeed, ever since the judgments of 2009 Fujimori has yet to publicly recognize his responsibility for these crimes, has not paid the civil reparations that he owes to the victims, and has not collaborated with the justice system to bring about the truth of the crimes and bring peace to the family members of the missing victims.

In this sense, a little over a year after the pardon was granted, it is very important that the Special Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court confirms the decision of October 3, 2018, and orders that Fujimori continue serving his 25-year sentence. However, politics always seems to get in the way of justice, and therefore the victims in these two cases seem to always need to fight against impunity. There is thus still a long way to go before we can talk about real justice, reparation and redress.

About the author

Maria Rodriguez is a volunteer legal advisor with the “Protection of Children, Women and Other Vulnerable Groups” project implemented by Lawyers without Borders Canada (LWBC) and the International Bureau for Children’s Rights as part of the volunteer cooperation program funded by Global Affairs Canada. The project focuses on improving the protection of the rights of children, women, and marginalized communities as well as on strengthening democracy and the rule of law through access to justice.

References

1 – Sala Penal Especial of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru, Judgment, Exp. A.V. 19-2001, April 7, 2009.

2 – See “Barrios Altos, Caso emblemático que contribuyó a revertir leyes de amnistía y la condena del expresidente Alberto Fujimori”, CEJIL. Retrieved from: https://cejil.org/en/barrios-altos; and “¿Qué ocurrió en Barrios Altos y La Cantuta?: A propósito de la audiencia ante la Corte IDH”, Instituto de Democracia y Derechos Humanos, February 5, 2018. Retrieved from: http://idehpucp.pucp.edu.pe/noticias-destacadas/ocurrio-barrios-altos-la-cantuta-proposito-la-audiencia-ante-la-corte-idh/.

3 – See “La Cantuta, The case that contributed to the conviction of Fujimori and the fight against impunity in Peru”, CEJIL. Retrieved from: https://cejil.org/en/cantuta-0; and “¿Qué ocurrió en Barrios Altos y La Cantuta?: A propósito de la audiencia ante la Corte IDH”, Instituto de Democracia y Derechos Humanos, February 5, 2018. Retrieved from: http://idehpucp.pucp.edu.pe/noticias-destacadas/ocurrio-barrios-altos-la-cantuta-proposito-la-audiencia-ante-la-corte-idh/.

4 – For more information about Peru’s armed conflict (1980-2000) see the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Peru available at: http://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/.

5 – Sala Penal Especial of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru, Judgment, Exp. A.V. 19-2001, April 7, 2009, párr. 717.

6 – “Para el 63%, PPK negoció el indulto a Fujimori para evitar la vacancia, según Ipsos”, La Republica, December 30, 2017. Retrieved from: https://larepublica.pe/politica/1164368-para-el-63-ppk-negocio-el-indulto-a-fujimori-para-evitar-la-vacancia-segun-ipsos

7 – “PPK renuncia a su cargo y afirma que habrá transición ordenada”, El Comercio, March 21, 2018. Available at: https://elcomercio.pe/politica/ppk-comunico-ministros-renuncia-difusion-videos-noticia-506143; and “Perú: renuncia el presidente Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (PPK) entre acusaciones de corrupción y sobornos”, BBC Mundo Noticias, March 21, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-43481060

8 – Article 118 (21) of the Constitution of Peru confers the discretional power to the President to grant pardons and commute sentences. These decisions are res judicata from the moment they are taken (See, Constitución Política de Perú de 1993 artículo 118. Retrieved from: http://www.pcm.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Constitucion-Pol%C3%ADtica-del-Peru-1993.pdf). As well, in the Internal Procedural Rules of the Presidential Pardons Commission there is no foreseen appeals process to challenge the final decision. (See, Reglamento Interno de la Comisión de Gracias Presidenciales, Resolución Ministerial Nº 0162-2010-JUS Lima, 13 de julio de 2010. Retrieved from: http://www2.congreso.gob.pe/sicr/cendocbib/con4_uibd.nsf/0BD5BECA2731827B05257B02006E5E00/$FILE/162-2010-JUS.pdf. Therefore, the only avenues that where available at the time were a possible administrative review (looking for the nullity the administrative decision) or taking the constitutional avenue (in the form of an AMPARO) to challenge the constitutionality of the decision. However, none of these mechanisms where per se a direct appeal to the decision that granted the pardon. For some analyses on the question of whether the granting of the pardon was subject to appeals or challenges, or not, see: “Raúl Ferrero: decisión de no indultar es inapelable”, Gestión Pe. June 9, 2013. Retrieved from: https://gestion.pe/peru/politica/raul-ferrero-decision-indultar-fujimori-inapelable-40372; “Víctor García Toma: “El presidente ya no puede anular su propia resolución, esto ya es cosa decidida”, Perú 21, December 25, 2017. Retrieved from: https://peru21.pe/politica/victor-garcia-toma-presidente-anular-propia-resolucion-esto-cosa-decidida-389577; and “El Indulto ya no se intocable”, La Republica, January 12, 2018. Retrieved from: https://larepublica.pe/politica/1169828-el-indulto-ya-no-es-intocable).

9 – I/A Court H.R., Case of Bulacio V. Argentina. Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 18, 2003. Series C No. 100, párs. 110 y 111 and I/A Court H.R., Case of Women Victims of Sexual Torture in Atenco v. Mexico. Prelimary Objection, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of November 28, 2018. Series C No. 371, pár. 267. See also article 1.1 of the American Convention of Human Rights.

10 – I/A Court H.R., Case of Barrios Altos v. Peru. Reparations and Costs. Judgment of November 30, 2001. Series C No. 87. Retrieved from: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_87_ing.pdf

11 – I/A Court H.R., Case of La Cantuta v. Peru. Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of November 29, 2006. Series C No. 162. Retrieved from: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/casos/articulos/seriec_162_ing.pdf

12 – Inter-American Court. Case Barrios Altos & Case La Cantuta Vs. Peru. Compliance and Monitoring of Judgements. Resolution of May 30, 2018 par. 15 Retrieved from: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/supervisiones/barriosaltos_lacantuta_30_05_18.pdf

13 – “Estándares del Derecho Constitucional peruano y del Derecho Internacional sobre la obligación de combatir la impunidad frente a crímenes de lesa humanidad”, Amicus Curiae, by Abogados Sin Fronteras Canadá, Fundación para el Debido Proceso, Human Rights Research and Education Centre, University of Ottawa, Clinique internationale de défense des droits humains, Université du Québec à Montréal, Instituto de Democracia y Derechos Humanos, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Comisión Internacional de Juristas, February 9, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.asfcanada.ca/site/assets/files/1114/amicus_curiae_corteidh_casos_barrios_altos_y_la_cantuta.pdf

14 – I/A Court H.R., Case of Barrios Altos and La Cantuta v. Peru. Monitoring Compliance with Judgments, Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, May 30, 2018. Retrieved from: http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/supervisiones/barriosaltos_lacantuta_30_05_18.pdf.

15 – “Anulan indulto humanitario a Ex Presidente Alberto Fujimori”, El Comercio, October 4, 2018. Retrieved from: https://elcomercio.pe/politica/alberto-fujimori-corte-suprema-anulo-indulto-otorgado-ex-presidente-noticia-564011.

16 – “Alberto Fujimori: así fue su traslado a una clínica tras anulación de su indulto”, El Comercio. Retrieved from: https://elcomercio.pe/politica/alberto-fujimori-traslado-clinica-anulacion-indulto-noticia-nndc-564170

17 – “Alberto Fujimori fue dado de alta tras 113 días y será trasladado a Barbadillo”, Gestion Perú. January 23, 2019. Retrieved from: https://gestion.pe/peru/politica/alberto-fujimori-dado-alta-113-dias-sera-trasladado-barbadillo-nndc-256577.

In action

Follow live achievements of our teams in the field.